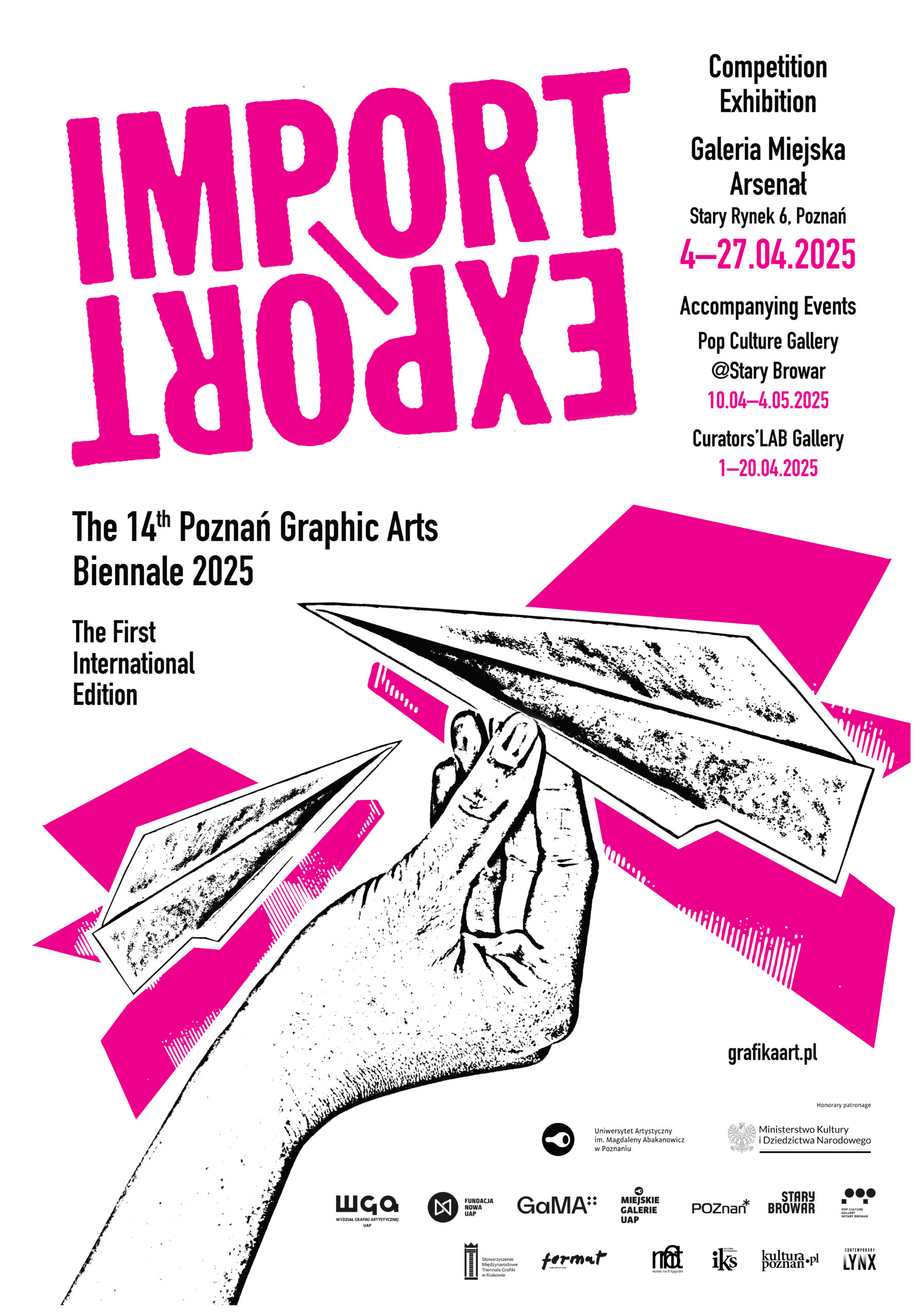

BIENNALE / SPRING 2025

The 14th Poznań Graphic Arts Biennale: IMPORT/EXPORT

THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL EDITION

Thank you to all participants! We’re thrilled to have received 917 submissions from 67 countries!

COMPETITION EXHIBITION

Municipal Gallery Arsenał

Stary Rynek 6, Poznań

4–27 April 2025

Opening: 4 April 2025, 6:00 pm

Connect with us on social media:

LAUREATES OF THE 14TH POZNAŃ GRAPHIC ARTS BIENNALE 2025

GRAND PRIX of the 14th Poznań Graphic Arts Biennale Poznań 2025

funded by the Mayor of the City of Poznań

20 000 PLN

Vinicius Libardoni – Brazil/Italy

for the artwork: The Sudetes

FIRST PRIZE of the Rector of the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts in Poznań

7 000 PLN

Marcin Lorenc – Poland

for the artwork: Written Drawings

SECOND PRIZE of the Dean of the Faculty of Graphic Arts of the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts in Poznań

5 000 PLN

Zofia Balbierz – Poland

for the artwork: Colorful Commute Stains

THIRD PRIZE of the Director of the Municipal Gallery Arsenał in Poznań

5 000 PLN

Małgorzata Gazda – Poland

for the artwork: The Pleasure of Failure

PRIZE of the Rector of the Collegium Da Vinci

1 500 PLN

Lola Staniuk – Poland

for the artwork: Echo I

HONOURABLE MENTION

Klaudia Borzęcka (Poland) for the artwork: Limit

Anna Pavlichenko (Ukraine) for the artwork: More Pain Ahead

Zuzanna Stempska (Poland) for the artwork: The Leftovers

Agata Perzyńska (Poland) for the artwork: Ars auro prior 1-10. Art More Precious Than Gold

Karolina Piotrowska (Poland) for the artwork: Tension

HONOURABLE MENTION from Contemporary Lynx

Bogna Lupińska – Poland

for the artwork: Where Do I Look?

HONOURABLE MENTION from Notes Na 6 Tygodni

Zuzanna Stempska – Poland

for the artwork: The Leftovers

Artists: Aleksandra Hryciuk, ANUnaran Jargalsaikhan, Zofia Balbierz, Adam Ejsmont, Agata Perzyńska, Aleksandra Piekarska, Aleksandra Ujazdowska-Bałdowska, Aliaksandra Smal, Anna Dąbrowska, Anna Mandziak, Anna Nawój, Anna Pavlichenko, Anna Wołek, Antonia Taralli, Aurelia Komorowska, Bogna Lupińska, Cullen Curtis, Cyprian Szablak, Damian Idzikowski, Daria Sukhina, Dominika Borek, Elitsa Dimitrova, Elkin Salamanca, Goyen Chen, Guanchu Zhu, Irma Holm, Ivona Pupačić, Jan Dyczko, Jan Gąsienicyn, Jan Stachowiak, Jarema Chyrzyński, Joanna Jagielska, Julia Latko, Julia Litwinek, Julia Maj, Julia W. Szagdaj, Julia Żmuda, Kamil Kocurek, Kamila Kościańska, Karolina Piotrowska, Katarzyna Tereszkiewicz, Kinga Grossmann, Klaudia Borzęcka, Klaudia Stańko, Laura Laviv, Lola Staniuk, Małgorzata Gazda, Marcin Lorenc, Maria Eross, Maria Rey, Mateusz Janik, Matylda Jaszczurka, Melisa Kajzerek, Mikołaj Czyżowski, Mikołaj Mroczkowski, Nadiia Sharova, Natalia Lewandowska, Nikola Radosavljević, Nina Natońska, Oksana Fedchyshyn, Oliwia Łukawska, Özgü Ayça Yıldız, Patryk Brzezicki, Renata Maria Gogol, Sandra Stojańska-Rekus, Urszula Michalecka, Valentin Sismann, Vasyl Savchenko, Vinicius Libardoni, Wiktor Wiater, Yibiao Qin, Zhenhao Ou, Ziad Abdel-Aal, Zofia Leszczyńska, Zoran Mishe, Zuzanna Stempska

Import/Export

The expanding global capitalist system creates a network of supranational connections, shaping the binary division of the world into the dominant core and the subordinated periphery. Areas in which civilizational and economic development does not keep up with the pace of the core are still influenced by outdated (archaic) forms of socio-economic organization. The slower paced development of the periphery is often explained by its insufficient integration with more economically advanced areas. However, we fail to observe that it is the global economic system, which is based on the accumulation of capital, that contributes to the emergence of this division and of backward regions, which are a ‘consequence of the polarising logic of the expansion of this system’.1

Each new state included in this supranational structure, usually because of conquest, is pushed to a peripheral position. In this way, the integrated economic system that is being created leads to the emergence of a hierarchy based on various specializations and degrees of professionalization. In the newly incorporated and less developed regions, production processes usually require a large input of labour and time, but they do not guarantee high profits. In addition, the peripheral economy is usually based on agriculture and the extraction of raw materials, with intensive exploitation of natural resources and labour. As a result, less affluent regions in the global economic system become dependent on more developed areas. The profitability of production in the periphery results from low costs, which are possible thanks to cheap or even slave labour. The export of cheap products from poorer regions is the key factor that influences the functioning of economic systems and deepens the phenomenon of polarization between the core and the periphery. As a result, differences in profits in individual regions arise, giving developed countries an advantage over less affluent areas. According to Immanuel Wallerstein, social polarization is a key element in creating this kind of dependency in the economic system, which is based on the accumulation of capital. This is caused not only by a delay in achieving the standards imposed by the core but also by the very structure of the system, which is based on these inequalities. Consequently, closing the gap and catching up with richer regions becomes impossible.

The economic system, supported by the political and social structure, also leads to the export of western/central patterns and models of behaviour to less affluent regions. This process is closely linked to cultural expansion, an example of which is the phenomenon of Eurocentrism. As the periphery, and the semi-periphery in particular, try to achieve the standards and organizational models set by the core, they obsessively compare themselves to developed countries and intensively adapt their cultural patterns. The process of importing social patterns and organizational structures in order to build one’s own identity is referred to as cultural self- colonization. It is defined through ‘the trauma of inferiority resulting from awareness of alienation from the Universal’.2 Thus, cultural phenomena in semi-peripheral areas are often described in relation to paradigms and trends established by the core.

In the context of the above considerations, it is worth paying attention to the concept of horizontal art history by Piotr Piotrowski. It can be interpreted as an attempt to neutralize the vertical approach, in which art trends are imposed by the dominant western culture.3 In the traditional, vertical model of cultural development, artistic phenomena spread from the core to the periphery. The export of artistic phenomena, and particularly how they are interpreted, significantly affects their reception in regions located outside the strict core. The concept of horizontal art history reveals a process resulting from the complexity of visual culture, which makes it difficult to indicate clearly which artistic phenomena were dominant in any period.

This allows simplifications and the superficial popularization of trends developing at any historical moment to be avoided.

The import and export of culture-forming artistic phenomena in the horizontal model support socialization while sustaining diversity, which makes it possible to show the complex human environment more thoroughly. This model of exchange is not limited to ‘products’ (which is typical of consumer culture) but focuses on active participation in a creative process and on searching for and propagating utopian visions.

Curator: Maciej Kurak

1 Marcin Starnawski, Przemysław Wielgosz, Kapitalizm nad przepaścią, społeczeństwa wobec wyboru. O krytycznych perspektywach analizy systemów-światów Immanuela Wallersteina, in: Immanuel Wallerstein, Analiza systemów-światów. Wprowadzenie, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog, 2007, p. XXV.

2 In reference to Alexander Kiossev, Jan Sowa, Fantomowe ciało króla. Peryferyjne zmagania z nowoczesną formą, Kraków: UNIVERSITAS, 2011, p. 21.

3 For more on this topic see e.g. Piotr Piotrowski, Globalne ujęcie sztuki Europy Wschodniej, Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, 2018.

JURY 2nd STAGE:

Sebastian Cichocki

A curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN). He has curated, among others, The Gleaners Society at EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial of Contemporary Art (2023) as well as the Polish Pavilions at the Venice Biennale, Gwangju Biennale, and Thailand Biennale in Chiang Rai. His curatorial practice focuses on artistic approaches that engage with climate activism, radical education, and agriculture.

Eulalia Domanowska

Director of the State Gallery of Art in Sopot, an artist, art historian, and curator, she has organized over 100 exhibitions, including those featuring Tony Cragg, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Henry Moore. Director of the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko from 2016 to 2019 and lecturer in art history. Author of numerous publications and former editor-in-chief of the Orońsko Quarterly. The initiator of the conference “Sculpture Today” and a participant in numerous conferences in Poland and worldwide. Specializes in art in public space and landscape. Member of AICA and IKT.

Anna Łazar

Curator, author, and translator. Creator of numerous exhibitions in Poland and abroad, including at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, the Arsenał Gallery in Białystok, and the Museum of Art in Łódź. Curator of the international artistic cooperation program Free Word (2022–2024). Former Deputy Director and Acting Director of the Polish Institutes in Kyiv and Saint Petersburg. Member of the Women’s Archive at IBL PAN and the Polish section of AICA.

Błażej Ostoja Lniski

A painter and graphic artist specializing in lithography, as well as a book, poster, and typeface designer. Professor dr. hab. at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where he leads the Lithography Studio. Dean of the Academy from 2012 to 2020. Currently serves as Rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and Chairperson of the Conference of Rectors of Art Universities. Honoris Causa Doctor of the Lviv National Academy of Arts and recipient of the Gold Gloria Artis Medal for Merit to Culture.

Marta Anna Raczek-Karcz

Art historian and cultural studies scholar, PhD in humanities, assistant professor at the Faculty of Graphic Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. Art theorist, critic, and independent curator collaborating with the National Museum in Krakow, the Manggha Museum, and MODEM in Debrecen. Jury member for graphic arts competitions in Poland and abroad. Since 2013, president of the SMTG in Krakow. Member of AICA and the Polish Cultural Studies Association. Author of publications on art, film, and digital media.

Magdalena Radomska

A post-Marxist art historian and philosopher, Assistant Professor at the Institute of Art History at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, and Director of the Piotr Piotrowski Center for Research on East-Central European Art. She has been a scholar at the Courtauld Institute of Art, Getty Foundation, ERSTE Stiftung, NCN, ELTE, and MTA. Author of books and numerous academic publications in several languages. Her research focuses on communist and post-communist art in Europe and the critique of capitalism in global art. Member of AICA, ASEEES, and OZZ. Her book Plural Subject: Art after the Crisis of 2008 – Shifting the Paradigm will be published by Routledge in autumn 2025.

Marek Wasilewski

An artist, art critic, and Professor dr. hab. at the University of the Arts in Poznań, Faculty of Animation and Intermedia. Former editor-in-chief of Zeszyty Artystyczne and Czas Kultury. Since 2017, director of the Arsenał Municipal Gallery. Member of AICA and recipient of scholarships from the British Council, Fulbright Foundation, and the Kosciuszko Foundation. Author of books on art, including Art in the Age of Populism.

JURY 1st STAGE:

Oskar Dawicki

Born in 1971. Polish multimedia artist specializing in performance art, video, photography, and documentation; also creates installations and objects. He lives and works in Warsaw. In 1996, he graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, where he studied painting under Professor Lech Wolski. During the 1990s, together with Radosław Nowakowski and Wojciech Kiwi Jaruszewski, he formed the group Tu Performance. Later, in 2001, along with Igor Krenz, Wojciech Niedzielko, and Łukasz Skąpski, he co-founded the Azorro group. Since 1994, he has been active as a performer, and since 1995, he has been known for his characteristic blue sequined jacket.

Lidia Głuchowska

Art and literary historian; head of the Department of History and Theory of Art at the Institute of Visual Arts, University of Zielona Góra. After her studies in Warsaw PhD degree from Humboldt University, Berlin. Curator; (co-)organiser of conferences in Poland and abroad. Author of over 100 articles, 4 books and (co-)editor of 5 international collective volumes.

Maciej Kozłowski

Born in 1976. Graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań. Laureate of the Grand Prix in the “Painting of the Year 2003” competition, co-publisher and co-editor of the zine “Glizda”. His works are included, among others, in the collection of the Greater Poland Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts. His areas of interest and artistic activity include graphics, painting, urban actionism, and publishing. Since 2019, lecturer at the Faculty of Graphic Arts and Visual Communication, and since 2024, at the Faculty of Artistic Graphics at the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts Poznań.

Mariya Plyatsko

An artist, head of the lithography workshop, and senior lecturer at the Department of Graphics and Book Art at the Institute of Printing art and Media Technologies of Lviv Polytechnic National University. A member of the jury of the 2023 Graphic Biennale in Poznań, “Error”. Organizer of printmaking graphic courses and promotes printmaking in Ukraine. Conducts artistic practices for military personnel and veterans in rehabilitation.

Organisation of the 14th Poznań Graphic Arts Biennale 2025: IMPORT/EXPORT:

Faculty of Graphic Arts of Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts Poznań

Co-organisation:

The Arsenal Municipal Gallery in Poznań

In co-operation with:

Stary Browar, Miejskie Galerie UAP

Curator:

Maciej Kurak

Exhibition design:

Mateusz Słociński

Coordination:

Olga Czechowska

Head of the organizing team:

Witold Modrzejewski

Organizing team:

Marta Chudy, Maciej Kozłowski, Monika Pich

In co-operation with:

Krzysztof Balcerowiak, Ireneusz Kozłowicz, Agnieszka C. Maćkowiak, Maja Michalska, Biuro Promocji i Działalności Kulturalnej UAP, Dział Techniczny UAP

Awards sponsors:

Rector of the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts Poznań, Dean of the Faculty of Graphic Arts of the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts in Poznań, Rector of the Collegium Da Vinci, Director of Municipal Gallery Arsenał in Poznań

Special thanks to Marek Wasilewski, Director of the Arsenal Municipal Gallery in Poznań

ACCOMPANYING EXHIBITIONS

Gene BY | Volha Savich

Curators’LAB UAP Gallery

ul. Nowowiejskiego 12, Poznań

1–20 April 2025

Curator: Ewelina Muraszkiewicz

Opening: 1 April 2025, 7:00 pm

Volha Savich is a resident of the PersPaktiv project. It was created out of the need to support people from the artistic community understood in a broad sense that originates from Belarus. ‘Gene BY’ is an artistic reflection on the blurring of individual identity in times of political fear, migration and the disintegration of community. Volha Savich focuses on the topic of anonymity in both the digital and social space, which is becoming a new form of functioning. Her works address the topic of uncertainty and suspension, revealing the cracks in how Belarusians can think about themselves and their belonging today.

Transit

Exhibition of the Laureates of the 13th Graphic Arts Biennale / ERROR

Pop Culture Gallery @ Stary Browar

ul. Półwiejska 42, Poznań

10 April – 4 May 2025

Curator: Agnieszka C. Maćkowiak

Artists: Gabriela Bałdyga, Oksana Fedchyshyn, Aleksandra Gigiel, Olga Ilicheva, Aleksandra Kaim, Anastazja Kramer, Gabriela Palicka, Borys Szadkowski, Martyna Wojciechowska

Opening: 10 April 2025, 6:00 pm

State institutions are necessary for economies based on the accumulation of capital to develop. Among other things, they allow monopolies to gain significant profits and accumulate resources more efficiently. They also enable the externalization of production costs by transferring them to a wider population, which is particularly visible in the con- text of exploitation of the natural environment (polluted rivers, the felling of trees, global warming). These institutions also transfer the costs associated with the construction of the necessary infrastructure supporting the development of economic enterprises to an entire community by imposing tax burdens on the general public, rather than on direct beneficiaries. They also protect the existing order and mitigate possible opposition from radical social groups dissatisfied with this system by establishing entities which regulate and implement the rights to express social discontent and provisions on how they can be used. State power also enables entrepreneurs of one country to expand beyond its borders by exerting influence on other countries, which becomes possible with the growing strength and importance of this country in the international arena. Hence, states – along with their borders – only seemingly hinder the flow of capital. In this context, establishing the right to free movement and transport also becomes important. As Alain Badiou notes, a division is made by determining an appropriate measure, which excludes uncountable elements: ‘Free circulation of what lets itself be counted, yes, and above all of capital, which is the count of the count. Free circulation of that uncountable infinity constituted by a singular human life, never!’.

Migration regulations aim to strengthen national narratives, which emphasize the importance of national belonging, which is necessary to maintain the global capitalist system. Therefore, as Immanuel Wallerstein notes, at the very beginning – just after the revolution, when socialist ideas had not yet been depraved – the communist state was internationalist, ‘committed to a belief in the evils of nationalism, of imperialism, and of Tsarism’ and positioned itself in opposition to capitalism. At the current stage of development, the global capitalist system needs both state regulations and new areas of exploitation to be efficient. Deruralization and the shrinking of areas that could be used to increase production efficiency – based on the reduction of the means necessary to achieve it (changing means of production) – perversely contribute to maintaining polarization and the dependence of peripheral regions on core countries.

Artistic phenomena take shape against the background of this economic system. Referring to the scheme proposed by Wallerstein, the works of artists from the ‘provinces’ are often interpreted – as Piotr Piotrowski notes – through the prism of the core. The resistance of artists from the Eastern bloc against the regime during the Cold War involved a creative attitude focused on the possibility of creating diverse forms of expression and thus opposition to the homogeneity preferred by the ‘communist’ authorities, which imposed socialist realism.

This artistic pluralism was a manifestation of creative individuality and the autonomy of art. It was a reaction to politically engaged and propagandistic art but, as an alternative attitude to socialist realism, it took on the character of political engagement. After 1989, taking full advantage of their creative freedom, artists from Eastern Europe referred in their activities to the values of the previous era, which could enhance the processes of socialization. Thus, they treated art as a useful tool, serving society more or less directly (socially engaged critical art, referring to modernism).

Against the background of these changes, an alternative model has been shaped within the global history of art. It focuses on intercultural and alter-globalist values, is free from domination and is conducive to creative activities of a utopian nature. This approach does not omit specific territories nor does it treat them as transit spaces which only serve the free development of the core.

Author: Maciej Kurak

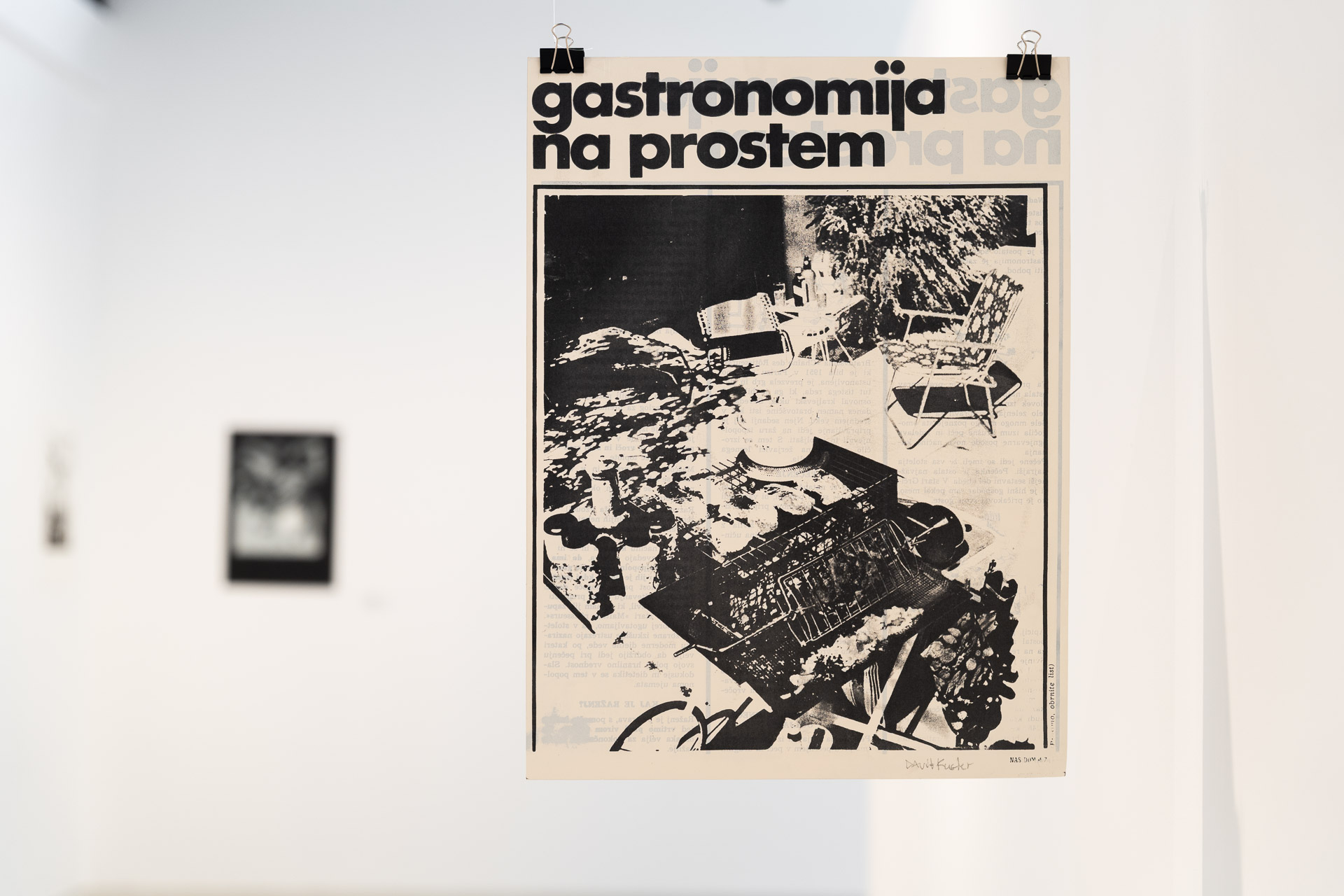

Import/Export. Ljubljana | ALUO Lecturers

Pop Culture Gallery @ Stary Browar

ul. Półwiejska 42, Poznań

10 April – 4 May 2025

Curator: Zora Stančič

Coordination: Witold Modrzejewski, Maja Michalska

Opening: 10 April 2025, 6:00 pm

Students: Ana Govc, David Kucler, Miha Majes, Nina Munih, Kalina Naskovski Perne, Tinkara Nemec Herkess, Maruša Pajnič, Ajda Podgorelec oraz Kristian Župan

Academic staff: Admir Ganić, Helena B. Tahir, Viktor Bernik ad. MFA, Arjan Pregl ad. MFA, Mojca Zlokarnik ad. MFA, Zora Stančič prof. nadzw. MFA

The exhibition curated by Zora Stančič features the artistic output of the lecturers of the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana (ALUO) – artists associated with graphic arts. Their works refer to the slogan ‘Import/Export’, which is the theme of the 14th Graphic Arts Biennale in Poznań. ALUO is a leading Slovenian institution in the field of visual arts, design and art conservation. Founded in 1945, it is distinguished by its interdisciplinary teaching and artistic programme, which is focused on critical theory, contemporary technology and sustainable development.

Authors of photos: Sonia Bober

Connect with us on social media: